By Matthew T. Eng

Naval Historical Foundation

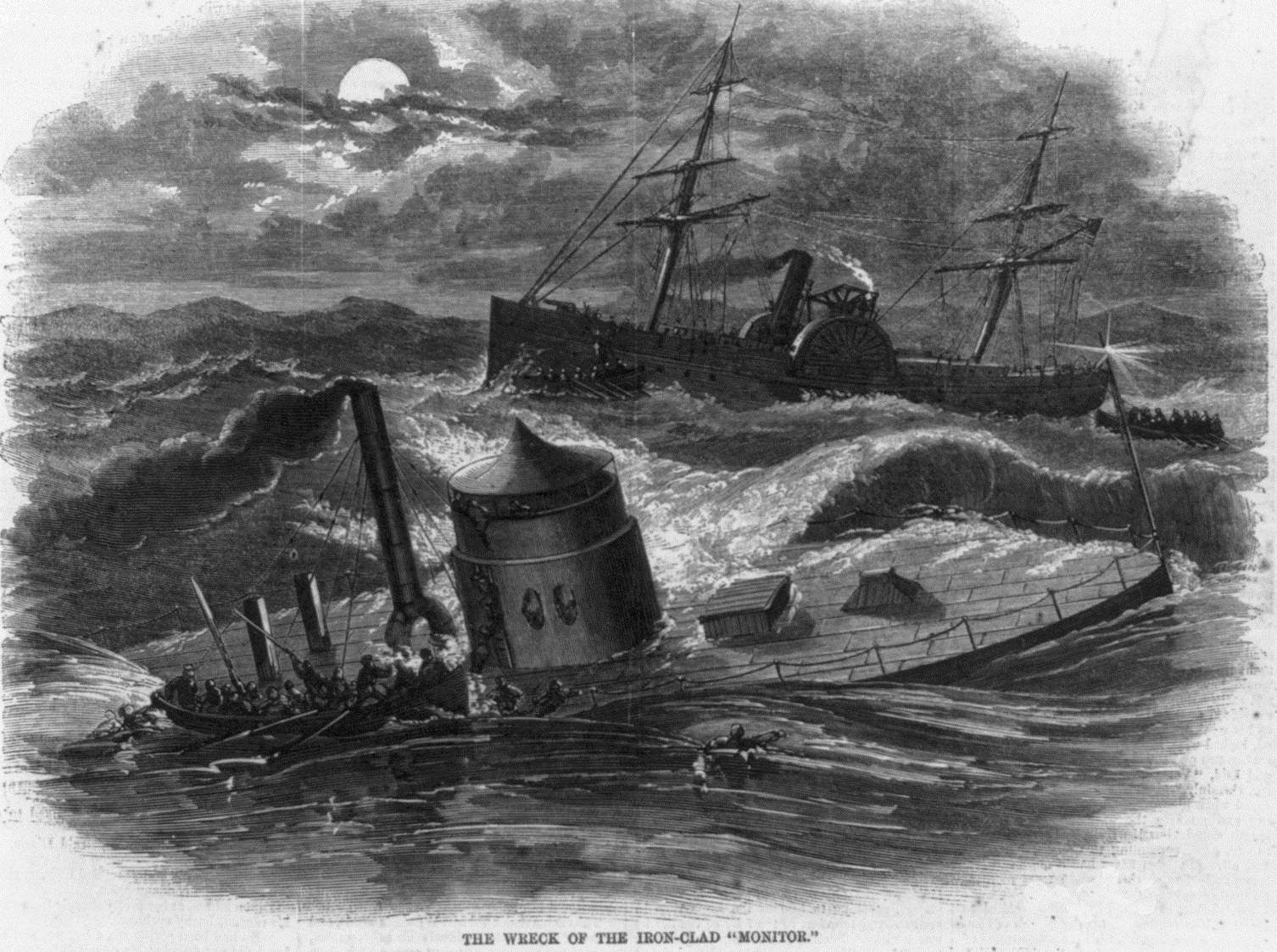

We are closing another calendar year on the Civil War Sesquicentennial. It is the last December of the war years. Civil War naval enthusiasts will note the importance of today’s date across the landscape of the social media blogosphere: the 31 December sinking of USS Monitor.

Naval Historical Foundation

We are closing another calendar year on the Civil War Sesquicentennial. It is the last December of the war years. Civil War naval enthusiasts will note the importance of today’s date across the landscape of the social media blogosphere: the 31 December sinking of USS Monitor.

Monitor put to sea

under tow from USS Rhode Island on

the final days of 1862. A violent storm soon developed off Hatteras, forcing Monitor’s Commanding Officer John P.

Bankhead to signal a red lantern to the crew of Rhode Island for help. The lamp

hung with the running lights on the turret, the highest point of the vertically

challenged vessel. By the time the Monitor

survivors arrived safely on board Rhode

Island, their beloved ship began to pitch and roll under the strain of the

sea. Sailors recall seeing the red light atop of the turret flickering in and

out in the distance as they began to break off. By 1:00 AM on 31 December 1862,

the red light was underneath the turbulent waves.

“We watched from the deck of the Rhode Island the lonely light upon the Monitor's turret – a hundred times we thought it had gone forever, – a hundred times it reappeared, till at last...it sank and we saw it no more."- Surgeon Samuel Gilbert Webber (USS Rhode Island)

The red lantern and several other important artifacts from

the ironclad are back on the surface. Resting underneath the waves are the

remains of the ship and the bodies of fourteen sailors. Two of their comrades

discovered inside the recovered turret now rest in Arlington National Cemetery.

Such A Heavenly Way to Die?

Significant dates are a tricky form of understanding

history, especially in today’s social media-centric society. Anybody can write

down or post about WHEN something happened in naval history. Maybe a few

historical photos will accompany the brief text. You may “like” it on Facebook.

Hell, you may even share it on your wall or tweet it to your followers. But the

learning stops there. The dialog dies. We can’t afford to do that when there is

so much more to talk about, especially Monitor.

It takes talent to convey to others WHY and HOW it happened.

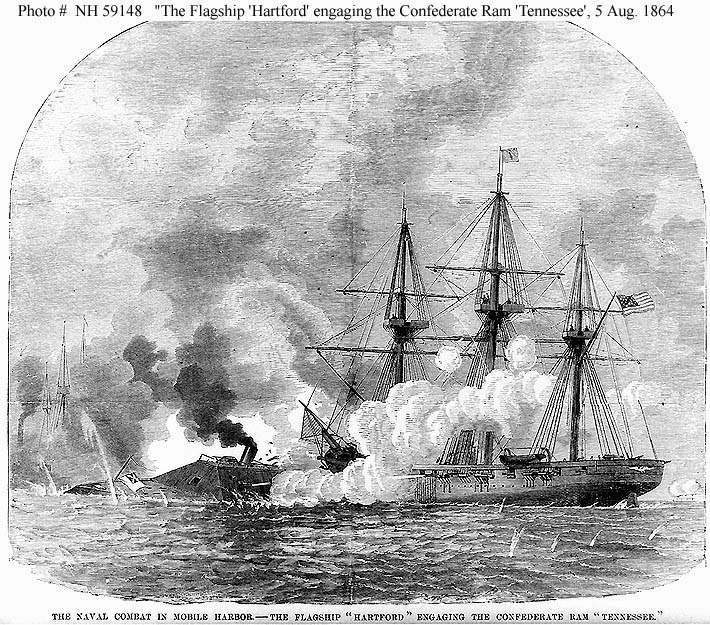

Most stewards of the craft are simply telling you when

something happened in the grand timeline of naval history. Fort Fisher falls in

January. Mobile Bay was an early August event. The Battle of Hampton Roads is

celebrated for two days every March. So much more happens in between a calendar

year and a time and place. Merely telling the general public about a

significant date in history seems like an empty gesture. The public demands and

deserves more. Thanks to a dedicated group of historians, museum specialists,

curators, and underwater archaeologists, we continue to learn more about

America’s first ironclad every day.

History in the

Darkened Underpass

It’s been a tough set of years to mark the current Civil War

commemoration. Anyone who tells you differently has not paid close attention to

the pulse of the general public. Controversy is a yearly event.

A centennial seems like a nice round number – one that is

easily recognizable to the general public. World War I fans are currently

reaping the benefits of this in the same way the public honored the recent War

of 1812 bicentennial. Looking back at 150 years is more difficult. These years

mark the halfway point on the road trip to the bicentennial. It is as if the

public is sitting in the back seat of the car, asking leading historians,

museum specialists, and authors “are we there yet?” We are there. In fact,

there is less than 150 days left in the entire sesquicentennial commemoration.

How will it fair during the 175th in 2036?

Monitor was not

immune to this harsh criticism in the wake of the Conservation Lab’s closure. The

year for Monitor began on 9 January with

news from the Washington Post that

the USS Monitor lab would close its

doors due to a lack of federal funding. The news shocked everyone, in and out

of the field. Many of the comments posted on the Post article were anything but helpful. Many questioned why we

support such aged history in the first place. Supporters of Monitor soon came to their aid when

funding proved short, calling for others to help preserve the lab and

artifacts. Thankfully, the lab reopened only a few months later this summer. Monitor was back, and the interest

continued to grow.

|

|

The Monitor

Center Reopens (Adrin Snider / Daily Press)

|

That interest stayed at this year’s 10th Maritime

Heritage Conference in Norfolk, Virginia. A special panel shed light on the

recent efforts and partnerships between the Mariners’ Museum, Monitor Conservation Lab, and NOAA.

Leading experts on the ship spoke positively about the future of the artifacts.

I had a chance to write a nice piece about some of their more recent artifact

conversation projects. The sea state was calm. The subject of Monitor and shipwreck history even came

up at this year’s World War I Centennial Conference at the MacArthur Memorial.

There is so much more to the mystery of Monitor

than a single date in time.

It would seem that the red lantern, which became a central

artifact in the discussion of the Monitor’s recovery, is still on. Dave Krop

and the fine folks at the lab are still doing the diligent work necessary to

preserve one of the Civil War’s most treasured relics.

Monitor is a

figurehead of American naval history. One may argue the ship’s supreme

importance within the timeline of naval history in general. Monitor is WHY and

HOW Civil War naval history is alive and well today. Such an important ship

deserves our respect and admiration.

“Well, the pleasure – the privilege is mine” to continue to

work with those who would see the red light never extinguished from the memory

of Monitor. Thank you to all who keep

it lit.